Quad atrophy following ACL injury is mind blowing. It wasn’t until I experienced this personally with my own ACL injury, that I really could grasp this strange and frustrating phenomenon. My quad index at 5 days post injury was 58%! I am now 17 days post ACL rupture. My quad is deflating daily, like a slow tire leak. I’m doing my best to work on my quad activation, but it never feels quite like it responds. Today, I worked leg extensions and could at best do half of what my non-affected side could do. It seemed like one of those dreams you have of being chased or wanting to run, but your legs…won’t…move.

Welcome to Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI).

Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition is a neural activation deficit of the quads. It sucks. It’s weird. It is a response to joint effusion, pain and joint damage. Though it is a protective mechanism initially, it persists and will make it brutally difficult to achieve a good quad index. AMI is most severe in the first few days after joint damage, plateaus mid-term (up to 6 months) and then slowly declines in the longer term (18-33 months);7 however, AMI may still be present years after joint damage. Residual levels of AMI (approximately 8% compared with controls) remain a mean of 4 years after arthroscopic menisectomy!9

Fortunately, there is evidence that the severity of AMI lessens over time. Snyder-Mackler found that 9 of 12 patients with ACL tear (average of 3 months post injury) had significant quadriceps inhibition but that no inhibition was present with chronic ACL rupture (average of 2 years postinjury).10 Similar findings occur post ACL reconstruction, with 6% difference in quad activation compared to controls at 18 months.11

The extent of AMI increases with the amount of joint damage. Quadriceps activation deficits may be seen following isolated ACL injury with AMI ranging from 3 to 8% when tested an average of 6 weeks to 31 months post injury. With additional joint damage (ligamentous, capsular, meniscal, and/or bony) in addition to ACL rupture, AMI of 15 to 41% can occur several months or years after injury.7

Further, AMI occurs in BOTH limbs with a unilateral injury. Quadriceps activation deficits as high as 16 to 24% have been documented in the uninjured limb among patients with extensive traumatic knee injuries.7 This is extremely important clinically, because we often compare function of the affected side with the contralateral side.

Mechanisms of AMI

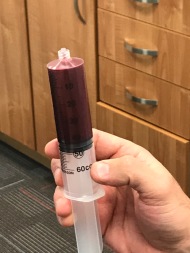

- Joint swelling. Even as little as 10cc, will induce quad inhibition.3 Draining the joint post injury is routinely done in our office but hasn’t always because sticking a large needle in the knee could be a source of infection. At the very least, my knee felt a ton better after 50cc of hemarthrosis was drained the day after I ruptured my ACL.

- Articular sensory receptors disruption. Konishi et al. suggest that loss of feedback from mechanoreceptors in ACL is the underlying mechanism of quad weakness.5 Damaged mechanoreceptors causes a gamma-loop dysfunction: at the level of the spinal cord, 1a afferent fiber (sensory fibers that respond to muscle length and velocity) feedback is altered and limits the quadriceps alpha-motorneuron depolarization.6 There are other spinal reflex pathways thought to be at play, such as flexion reflex, H-reflex and group I nonreciprocal (Ib) inhibitory pathway,6 but that is way beyond this blog AND my brain. Injecting anesthetic into the infused joint will decrease AMI as well as future AMI with subsequent joint effusion, further supporting the role of mechanoreceptors in the joint.3

- Corticomotor Contribution. Muscle contraction can be initiated through the excitation of descending corticomotor tracts.7 After ACL reconstruction, Inadequate excitation of descending corticomotor tracts may negatively affect voluntary activation, which could limit muscle-strength development.8

That is all super interesting, but how can we mitigate AMI??

We work with patients pre-operative in order to wean from crutches (if using them), walk without a limp, achieve full extension and perform a straight leg raise without extensor lag. This is typically achieved between 1-3 visits and the patient is able to schedule surgery, if they elect to go the surgical route. Now I ask, is this enough?

I have a different perspective on AMI now that I’ve experienced it. If you don’t have a patient explore different options to strengthen their quads, they may only be developing great compensatory strategies that may never go away. Take a squat, for instance. I feel NO activation of my quads. Great butt workout, but poor quad workout. Do patients understand what they should be trying to do? My guess is that they do not. I also struggled to do concentric single leg extensions on a leg extension machine. I could feel my quads fire with heavy eccentric work on the leg extension, provided I use my unaffected side to assist concentrically. Through trying different exercises: Bulgarians squats, split squats, reverse lunges with glider discs, isometrics at various knee flexion angles, single leg squats, etc., I’ve discovered what works best for me. It may not be the same for everyone, so our job as physios is to help find the one exercise that facilitates the quad BEFORE surgery. After surgery, we will be dealing with pain inhibition, limited knee flexion and more knee effusion.

I also augment my pre-hab with Neuromuscular Electric Stimulation (NMES). There is good evidence that NMES is an integral part of the rehabilitation pre and post ACLR.10 A benefit of NMES is that it directly recruits the motor neurons to produce better quadriceps strength gains than exercise alone.2 The most common protocol used is described by Fitzgerald1. Of note, NMES is not likely to change AMI itself, but will reduce quad atrophy post injury.7

Fitzgerald Protocol:

Patient seated with hip in 90 degrees flexion and knee in 60 degrees of flexion

1 electrode placed on proximal vastus lateralis and the other distal vastus medialis

2500 Hz (AC)

75 bursts per second

2 second ramp up and 2 seconds ramp down

10 seconds stimulation, 50 seconds rest (10 contractions total), 2x/week

Amplitude: high enough to provide tetanic contraction with visual superior glide of patella

Parameters Defined

Frequency (Hz): Describes FORCE generation. Minimum required for tetany (20-30Hz). Higher frequencies cause muscle fatigue and discomfort.

Waveform: describes the SHAPE of one cycle of current: biphasic, asymmetric, symmetric, monophasic, DC, pulsed, burst AC, etc. Biphasic Asymmetric most often used for max quads force production. Usually fixed on units.

Pulse Width (µs): describes LENGTH of pulse. Strongest muscle contractions with 300-400 µs pulses, but will also stimulate sensory fibers. Can adjust for comfort.

Duty Cycle: relates to fatigue and displayed as ratio. If higher frequency causes fatigue, try increasing the rest period.

Ramp: with higher intensity, use a longer ramp for comfort.

Along with quad strengthening and NMES, using cryotherapy immediately following injury will help with both effusion and pain. As far as immediately reducing AMI, 30 minutes is enough to reverse decline in quad activation up to 30 minutes following removal of the ice.7 There may be opportunity to use cryotherapy before exercise. I find cryotherapy effective in the first week post injury or surgery, but use of a compression sleeve is more effective long term. A compression sleeve made from Tensogrip is my preference initially, and often I have patients use an over the counter knee sleeve post-surgery once their effusion is minimal.

To counteract cortocospinal involvement of AMI, biofeedback and transcranial magnetic stimulation and have been suggested. I won’t expand on those tools, as physios do not have access to those modalities.

In summary, AMI sucks. It’s weird. Help your patients find the best way to facilitate their quads, even before surgery. Use ice and NMES as adjuncts. Consider compression. And, DO NOT forget about the other limb.

Image: Walmart.com

References

- Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Sep;33(9):492-501

- Palmieri-Smith RM, Thomas AC, Wojtys EM. Maximizing quadriceps strength after ACL reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2008 Jul; 27(3):405-24, vii-ix.

- Wood L, Ferrell WR, Baxendale RH. Pressures in normal and acutely distended human knee joints and effects on quadriceps maximal voluntary contractions. Q J Exp Physiol. 1988 May; 73(3):305-14

- Iles JF, Stokes M, Young A. Reflex actions of knee joint afferents during contraction of the human quadriceps. Clin Physiol. 1990 Sep; 10(5):489-500.

- Konishi Y, Fukubayashi T, Takeshita D. Possible mechanisms of quadriceps femoris weakness in patients with ruptured anterior cruciate ligament. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002 Sep;34(9):1414-8.

- Rice DA, McNair P, Lewis G. Mechanisms of quadriceps muscle weakness in knee joint osteoarthritis: the effects of vibration on torque and muscle activation in osteoarthritic and healthy control subjects. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2011;13:R151

- Rice DA, McNair PJ. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Dec; 40(3):250-66.

- Pietrosimone B, Lepley A, Ericksen H, et al. Neural excitability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2015 Jun; 50(6):665-674.

- Becker R, Berth A, Nehring M, Awiszus F. Neuromuscular quadriceps dysfunction prior to osteoarthritis of the knee. J Orthop Res 2004;22(4):768-73.

- Snyder-Mackler L, De Luca PF, Williams PR, Eastlack ME, Bartolozzi AR 3rd. Reflex inhibition of the quadriceps femoris muscle after injury or reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76(4):555-60.

- Urbach D, Nebelung W, Becker R, Awiszus F. Effects of recon- struction of the anterior cruciate ligament on voluntary activa- tion of quadriceps femoris a prospective twitch interpolation study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83(8):1104-10.

Leave a comment